As Bullies Go Digital, Parents Play Catch-Up

Ninth grade was supposed to be a fresh start for Marie’s son: new school, new children. Yet by last October, he had become withdrawn. Marie prodded. And prodded again. Finally, he told her.

“The kids say I’m saying all these nasty things about them onFacebook,” he said. “They don’t believe me when I tell them I’m not on Facebook.”

But apparently, he was.

Marie, a medical technologist and single mother who lives in Newburyport, Mass., searched Facebook. There she found what seemed to be her son’s page: his name, a photo of him grinning while running — and, on his public wall, sneering comments about teenagers he scarcely knew.

Someone had forged his identity online and was bullying others in his name.

Students began to shun him. Furious and frightened, Marie contacted school officials. After expressing their concern, they told her they could do nothing. It was an off-campus matter.

But Marie was determined to find out who was making her son miserable and to get them to stop. In choosing that course, she would become a target herself. When she and her son learned who was behind the scheme, they would both feel the sharp sting of betrayal. Undeterred, she would insist that the culprits be punished.

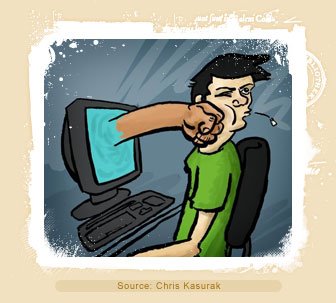

It is difficult enough to support one’s child through a siege of schoolyard bullying. But the lawlessness of the Internet, its potential for casual, breathtaking cruelty, and its capacity to cloak a bully’s identity all present slippery new challenges to this transitional generation of analog parents.

Desperate to protect their children, parents are floundering even as they scramble to catch up with the technological sophistication of the next generation.

Like Marie, many parents turn to schools, only to be rebuffed because officials think they do not have the authority to intercede. Others may call the police, who set high bars to investigate. Contacting Web site administrators or Internet service providers can be a daunting, protracted process.

When parents know the aggressor, some may contact that child’s parent, stumbling through an evolving etiquette in the landscape of social awkwardness. Going forward, they struggle with when and how to supervise their adolescents’ forays on the Internet.

Marie, who asked that her middle name and her own nickname for her son, D.C., be used to protect his identity, finally went to the police. The force’s cybercrimes specialist, Inspector Brian Brunault, asked if she really wanted to pursue the matter.

“He said that once it was in the court system,” Marie said, “they would have to prosecute. It could probably be someone we knew, like a friend of D.C.’s or a neighbor. Was I prepared for that?”

Marie’s son urged her not to go ahead. But Marie was adamant. “I said yes.”

Parental Fears

One afternoon last spring, Parry Aftab, a lawyer and expert on cyberbullying, addressed seventh graders at George Washington Middle School in Ridgewood, N.J.

“How many of you have ever been cyberbullied?” she asked.

The hands crept up, first a scattering, then a thicket. Of 150 students, 68 raised their hands. They came forward to offer rough tales from social networking sites, instant messaging and texting. Ms. Aftab stopped them at the 20th example.

Then she asked: How many of your parents know how to help you?

A scant three or four hands went up.

Cyberbullying is often legally defined as repeated harassment online, although in popular use, it can describe even a sharp-elbowed, gratuitous swipe. Cyberbullies themselves resist easy categorization: the anonymity of the Internet gives cover not only to schoolyard-bully types but to victims themselves, who feel they can retaliate without getting caught.

But online bullying can be more psychologically savage than schoolyard bullying. The Internet erases inhibitions, with adolescents often going further with slights online than in person.

No copyright infringement intended. For educational, non-commercial purposes only.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.